Understanding Trade Wars

The US Trade Representative (USTR) made public the framework it had used for calculating “reciprocal tariffs.” The aim of these newly-introduced tariffs is to eliminate the US (chronic) bilateral trade deficits which are seen as “bad” and a loss to the US. USTR then got busy to “correct” this bad. However, USTR’s approach misinterprets both the concept of reciprocal tariffs and the underlying macroeconomic drivers of trade (im)balances.

1- Starting from the wrong scorecard

The current US administration views trade deficits as a sign that the United States was “losing” in global trade, arguing that they reflect unfair practices and economic weakness. However, economists widely disagree with this interpretation. When a country imports more than it exports, it’s often because consumers have high purchasing power and businesses are investing in foreign goods, services, or capital equipment. In return, foreign countries typically invest in the deficit-running nation’s assets, fueling innovation, job creation, and infrastructure. Rather than being a red flag, a trade deficit can signal global confidence in the country’s economy, showing that it’s an attractive place to spend, invest, and grow.

2- Mis-using of the term “reciprocal tariffs”

In economics and standard trade policy, reciprocal tariffs mean matching the tariffs other countries impose on your exports, nothing more. It’s about symmetry (or reciprocity) in tariff levels, not trying to balance trade deficits.

3- Mis-diagnosing the true drivers of trade deficits

Trade deficits are not primarily caused by tariff policies. They reflect deeper macroeconomic forces. Specifically, trade deficits reflect the gap between national savings and investment. The key identity here is:

Current Account = Exports – Imports + Net Income Transfers = National Savings – Investment

This means a country runs a current account (or trade) deficit when it spends more than it earns, financing that gap by borrowing from abroad (i.e., using other countries’ savings). Tariff levels barely affect this big-picture dynamic.

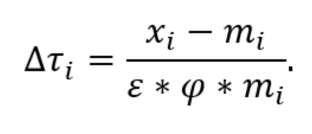

We now come to the approach that USTR has introduced. USTR proposes a formula:

where:

∆τᵢ = change in tariff rate

ε < 0 = price elasticity of imports φ > 0 = tariff pass-through to prices (if equal to 1 then full pass through, if less than 1 then partial pass-through)

mᵢ = imports from country i

xᵢ = exports to country i

This approach:

- Ignores global supply chains, where imports (like parts and components) are essential for US production and exports.

- Ignores macro fundamentals, like national saving and investment behavior.

Also, the math only works if ε × φ = 1. USTR assumes:

- ε = 4, which is reasonable when the interest is in the long run elasticities. Many studies confirm this.

- φ = ¼, citing Cavallo et al. (2021). But this is misleading—Cavallo himself clarified on X (Twitter) that his paper found φ = 0.945, not ¼! This assumption automatically reduces the denominator by a factor of 4 leading to a reciprocal tariff that is 4 times larger than it needs to be, even when applying USTR’s own formula.

Unsurprisingly to the majority of economists, this “reciprocal tariffs” policy path:

- Worsens market performance (worst since COVID)

- Risks re-igniting inflation

- Raises the specter of stagflation (high inflation + low growth)

But, don’t just take our word for it. Here’s a precedent:

A digression: what history tells us

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act (1930) is one of the most infamous examples of tariff policy gone wrong, often cited as a cautionary tale. The Act that was passed during the onset of the Great Depression with the objective of protecting American farmers and industries from foreign competition. It imposed high tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods, raising average US tariffs to nearly 60% on dutiable imports—among the highest in US history.

Actual Outcomes:

1. Retaliation by other countries

- A global trade war then ensued with dozens of countries, including Canada, France, and the UK, retaliating with their own tariffs.

- US exports dropped by more than 60% between 1929 and 1933.

2. Collapse in world trade

- Between 1929 and 1934, world trade fell by around 66%.

- Though the Great Depression had already begun, Smoot-Hawley deepened and prolonged it, especially globally.

3. Negative Impact on the US Economy

- While some industries briefly benefited from reduced competition, the broader economy suffered.

- Farmers faced retaliatory tariffs that devastated export markets.

- Manufacturers and exporters were hit hard as global demand shrank.

Economic historians widely agree it worsened the Great Depression.

4. Long-term damage to US trade policy

- The US shifted course in 1934 with the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, which began lowering tariffs.

- It marked a turning point toward trade liberalization that lasted for decades and until January 2025.

Another digression: are trade deficits “bad”?

NO

The current US administration views trade deficits primarly as a sign that the US was being taken advantage of in international trade. They describe them as evidence that other countries were ‘winning’ at America’s expense by exporting more to the US than they import in return.

Here are five reasons why trade deficits, in and by themselves are not necessarily a bad thing:

1. A trade deficit means a country imports more goods and services than it exports. On the surface, that sounds like the country is “losing,” but it’s not that simple. Why this can be fine?

- Americans buy affordable goods from abroad, which raises living standards.

- Companies and consumers get greater variety, lower prices, and higher quality from global options.

2. Trade deficits also reflect capital flows and investment. This is the most important (but least understood) part.

Trade deficit = Capital account surplus. This means when the US runs a trade deficit, foreigners are investing more money in the US than Americans are investing abroad. This matters a lot since:

- Foreigners buy US stocks, bonds, property, and businesses.

- That inflow of capital can fund innovation, infrastructure, and job creation.

- The US dollar remains a global reserve currency, so many countries prefer to invest in the US rather than demand goods in return.

3. Trade deficits can also reflect strong domestic demand. They often increase when a country’s economy is strong, because (1) people have more income and consume more, including imports, and (2) businesses import capital goods to expand operations.

A growing economy often pulls in more imports, so the trade deficit grows, not because things are bad, but because demand is strong.

4. Countries don’t trade, people and businesses do. Indeed, trade is a positive sum game between nations. For example: a US company buys German machinery because it’s the best tool for the job. That’s good business, not a national “loss.”

5. Countries with trade surpluses aren’t always better off:

- Germany has been running one of the world’s largest trade surpluses for decades driven by low household consumption and high corporate savings; and in recent quarters its economy has been witnessing flat or negative growth.

- Japan has had a trade surplus for decades, but its economy has faced stagnation, low domestic demand and persistent deflationary pressure; Japan’s surplus drivers are: high savings and limited domestic consumption.

- Switzerland’s growth has been slow and uneven and at the same time has been running surpluses in its trade account driven by external demand and not necessarily domestic strengths. And,

- of course, let us not forget Russia that since 2022 has been running trade surpluses driven by a collapse in its import and not export strengths.

Examples of other countries that have been running trade deficits and their growth performance:

| Country | Trade Balance | Growth/Strength |

|---|---|---|

| US | Chronic deficit | High innovation, strong investment |

| Australia | Past chronic deficits | Long-term growth, resource-rich |

| UK | Chronic deficits | Strong services, global capital hub |

| Turkey | Recurrent deficits | High but volatile growth, now more fragile |

| India | Chronic deficit | Fast-growing, fueled by domestic demand |

But when can a trade deficit be a problem? There are scenarios where it can be concerning:

- If it’s driven by excessive debt or unsustainable consumption.

- If it coincides with de-industrialization or structural unemployment.

- If it reflects loss of competitiveness without offsetting benefits.

But in most developed countries, especially the US, it’s not a red flag by itself.

Bottom Line: A trade deficit is like a team recruiting top players from other countries. The team “imports” talent instead of only developing it locally. If those players help the team win championships, the net benefit is clear, even if they’re not homegrown.

[1] Cavallo, Alberto, Gita Gopinath, Brent Neiman, and Jenny Tang. 2021. “Tariff Pass-Through at the Border and at the Store: Evidence from US Trade Policy.” American Economic Review: Insights 3 (1): 19–34.

Related Insights

Contact us

Subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe now to receive our latest news